Last week a somewhat fascinating article was published by the New York Times discussing forensic DNA phenotyping, a new(ish) technique that allows for (as popular media would say) a person’s face to be reconstructed from only their DNA. It sounds almost science fiction-esque doesn’t it?

Media interest in the topic appears to have been resurrected over the last couple of months by the use of DNA phenotyping by law enforcement officers in Colombia, South Carolina, investigating the unsolved 2011 murder of Candra Alston and her daughter Malaysia Boykin. Investigators hired the services of an independent company to carry out DNA phenotyping on DNA recovered from the crime scene years before, resulting in the production of the apparent face of the suspect.

This is not novel, ground-breaking work. In fact the whole concept of this technique has been floating around for a few years now (though this was presumably the first case in which a face reconstructed solely from DNA was presented to the general public).

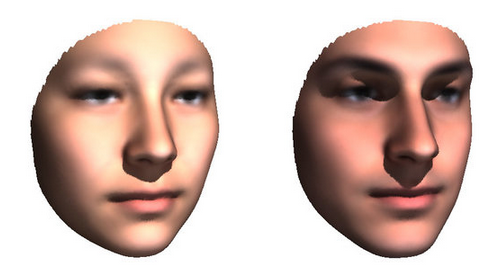

But just what actually is DNA phenotyping? As you may or may not recall, a phenotype is a physical characteristics which is the result of genetics, for instance the colour of one’s hair, eyes or skin. DNA phenotyping essentially attempts to determine physical traits such as these using only genetic material. This is based on the idea that certain genes are contributors to particular characteristics. Theoretically, this could be such a powerful tool for investigators, forensic, historical and medical investigators alike. Imagine a piece of software which is simply fed a DNA profile and spits out the face of your perpetrator (viewing it in a very black box manner of course). A face which could then be compared to existing mugshots of criminals or circulated to trigger recognition. Or the reconstructed face of a member of some ancient civilization. The possible applications are exciting and plentiful.

But it is of little surprise that, since the publication of this work over the last few years, numerous accounts emerged in the media blowing the results way out of proportion. If one were to Google DNA phenotyping, it is easy to believe it is a well-established technique often used in legal investigations around the world. In reality, this is a technique that is not permitted in court and in fact some countries have outright banned the use of DNA phenotyping (perhaps more for ethical purposes than concerns over accuracy). A research team at Penn State University in the US, led by Peter Claes and Mark Shriver, has been conducting research into this field of work. Despite the promising results published by the group, it has been made clear that the work so far provides an “analytical framework” but considerable further research is needed. Before any claims are made that scientists can reliably re-create a face from DNA, one must pay attention to the current lack of knowledge, inaccuracies and issues linked with DNA phenotyping, unfortunately often ignored by the media.

There are obviously clear ethical concerns associated with such techniques. Unsurprisingly, concerns over the possibility of racial profiling occurring have been raised. The images produced by DNA phenotyping methods have been referred to as being “generic” and could easily draw investigators down the wrong path as they focus solely on a particular physical characteristic suggested by this method. But on the other hand, could an eyewitness account, which are often famed for being ripe with inaccuracies, not also lead to such problems, should the eyewitness state the race of the person they saw?

Ethics aside, the accuracy of the technique is no doubt at the forefront of most people’s mind. Undoubtedly the face that is reconstructed can only ever be a kind of estimation based on the information available, being unable to take into account a whole array of factors that go beyond DNA. Dyed hair, hairstyle, facial piercings, tattoos, accessories, scars, even down to a person’s characteristic facial expressions which can wildly change the appearance of a face. Many genes are known to contribute to the development of a person’s face and the appearance of certain characteristics, and these genes can be targeted in this kind of work. But it does not take an expert in genetics to conclude that there are equally many genes that may contribute to appearance that we do not know about. So how accurate can this technique really be (at this point in time anyway)? And regardless of the actual accuracies (or inaccuracies, if you wish) of this technique, somewhat equally as important is how people actually perceive it. Anyone with the slightest interest in forensic science is no doubt aware of the so-called “CSI effect”, which has raised concerns over how lay people perceive scientific (or sometimes even unscientific) techniques. Is it plausible that, should DNA phenotyping be accepted into a courtroom, members of the jury will see “DNA” and assume it must be just as trustworthy as established DNA profiling techniques?

Despite the possible benefits of this technique, there is ultimately currently no way only the DNA of an individual can be used to reconstruct their face.

Thus this is a technique still under research, not yet developed enough to actually be used in legal investigations. And yet, in the United States at least, various independent companies are offering DNA phenotyping services. The law enforcement agency referred to at the beginning of this post in fact used one of these services. The results of these companies list a range of biological and physical attributes, including sex, skin colour, eye colour, hair colour, probable ancestry, and even if the suspect is likely to have freckles! It has even been suggested that genetic analysis could be a predictor of a person’s age. There is an array of factors that can affect a person’s appearance that do not necessarily have anything to do with their genetics, and a person’s DNA can in no way account for this.

These facts by no means aim to take anything away from the technique. DNA phenotyping undoubtedly can unlock entirely new routes of investigation for law enforcement officers, and it has been successfully used in a number of cases. Even if its use would not currently be accepted as evidence in court, it may still provide law enforcement with new investigative leads if other lines of inquiry have been exhausted.

Although the concept of DNA phenotyping emerged years ago and made slow progress, in the last couple of years research and interest appear to have boomed. It is a fascinating topic with huge potential, but it is ripe with practical and ethical concerns that will no doubt bring about some very intriguing debates. I am sure we will be hearing much more about this in the coming years.

References

Claes, P. Shriver, M D. Establishing a multidisciplinary context for modelling 3D facial shape from DNA. PLos Genet. 10 (2014).

Claes, P. Hill, H. Shriver, M D. Toward DNA-based facial composites: preliminary results and validation. Forensic Sci Int Gen. 13 (2014), pp. 208-216.

New Scientist. Genetic mugshot recreates faces from nothing but DNA. [online][Accessed 02 Mar 2015] Available: http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22129613.600-genetic-mugshot-recreates-faces-from-nothing-but-dna.html#.VPSBpvmsV8E

The New York Times. Building a Face, and a Case, on DNA. [online][Accessed 02 Mar 2015] Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/24/science/building-face-and-a-case-on-dna.html?ref=science